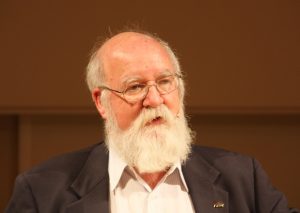

Interview with Daniel Dennett

Posted on: in Philosophy,Science by .

Tags: Dennett, Interview, philosophy

Interview conducted Tuesday 18th June 2019 by Henry Shevlin. Transcript lightly edited for clarity and flow. Click to listen on Soundcloud or Spotify.

Professor Dennett will need no introduction for many of our listeners. A giant of contemporary philosophy with interest in consciousness, freewill, evolution and religion, he’s written some 18 books and scores of articles including works like Elbow Room, Consciousness Explained and Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. He’s Co-director of the Centre for Cognitive Studies and the Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy at Tufts University.

Professor Dennett, perhaps you could begin by discussing your view of consciousness. You’ve referred to consciousness as a user illusion. Could you say a bit more for our listeners about what you mean by that?

DCD: Sure. Think of your smartphone, your mobile, you don’t know what’s going on inside that when you use an app. There’s a user illusion which has been brilliantly designed to simplify life so that with a few touches, a few nudges, a few button presses, you can do whatever you want. That’s a user illusion. That’s where the term comes from.

Notice, it’s a good thing. It’s a useful thing. You’re not the victim of an illusion. You are the beneficiary of an illusion. Evolution has done the same job of designing really all living organisms, especially mobile ones, ones that locomote, by simplifying the world for their benefit. That’s why we see colours. Colours aren’t out there as such. There wouldn’t be colours without colour vision. It’s the software and hardware that carves the world into colours – for instance.

“You’re not the victim of an illusion. You are the beneficiary of an illusion. Evolution has done the same job of designing really all living organisms by simplifying the world for their benefit.”

This is just the beginning of the idea and it’s a much more potent idea than that. We are the pilots of our bodies, so think of us as sitting in the cockpit but there’s no screen that we’re looking at. There doesn’t have to be a screen. They don’t have to be buttons cause we don’t have any fingers in there to push the buttons. All of the work that would be done by that homunculus sitting in the control room has to be distributed around into various brain processes.

None of those processes are in themselves conscious, but they create the illusion in others and in you, that you’re conscious. And it’s a benign illusion. It’s true in its own way, in the same way the apps on your cell phone. You really have those apps. They really do what they do. It’s just that you’ve got to simplify the hugely over-simplified and sort of metaphorical access to what’s actually going on. The same thing as what happens in your brain.

HS: So I think some of our listeners might balk at the idea of consciousness as being an illusion. People talk about the appearance-reality distinction and consciousness is sometimes taken to be just the appearances themselves. You might think the idea of consciousness as an illusion doesn’t make much sense because it’s still there even if it’s just an appearance. How would you go about working through someone who’s stuck with this misconception?

DCD: There’s a number of different ways. I’ll try going in the back door. They probably wouldn’t have much trouble with the idea that when you and I talk, I have a user illusion of your consciousness – incomplete, because I don’t have access to your inner thoughts. But as you talk to me, I get a pretty good idea of what’s going on in your mind and you can want me to have a good idea.

And so, each of us has a sort of model of the other as a conscious agent. Your consciousness is my user illusion of you and my consciousness is your user illusion of me. So the second person point of view comes first. Then we can turn that around and see that moreover, I can get access to myself really the same way I can get access to you by asking myself questions and seeing what I say. When I probe my own mind, which we human beings do all the time. We are always poking and prodding and shouting and getting ourselves to think things and not think things are trying to get us not to think things. What we’re doing is manipulating our brains. Thanks to the user illusion that we have.

HS: In your latest book, From Bacteria To Bach and Back you mentioned the progress that’s been made in the science of consciousness, which you’ve obviously been very involved with all the way back to your early work. Are you open to this possibility, though, that science could end up vindicating some of our intuitive or folk notions of consciousness? Or is that something that’s already been ruled out by the theoretical work you’ve done?

DCD: I think some of our ‘pet’ intuitions have been ruled out. There might’ve been a control room where the homunculus inside, it’s not self-contradictory. In fact, the film, Men in Black has this wonderful scene where they open up the face of the corpse in the morgue and it turns out to be a giant puppet and there’s a little green man sitting in the control room. That’s the Cartesian theatre. Nothing incoherent about that story.

But when we look inside, that’s not what we find. Empirically, we know there’s no control room, there’s no screen, there’s no homunculus. We’ve got to find another way of getting all that work done. We’re making great progress on that. That’s what I call the hard question. How does that work get done? Everything that apparently is done by the ego, the inner witness, how does all that work get done in the brain?

We’re making great progress on that. But the first thing you have to start with is there isn’t a show going on in your head. There just seems to be.

HS: One area where you might think the science of consciousness has been slightly at at least superficially at odds with previous claims you’ve made is the idea of global activation discussed by thinkers and researchers like Stanislas Dehaene. Now these things obviously have a lot in common with your early work. I believe you coined the phrase, “fame in the brain”, which has a huge amount in common with the idea of global activation, but you also have been sceptical of the idea that there might be a finish line in conscious processing, whereas on some views at least of the way global activation works, it does look a little bit like a finish line. It looks like a determinant moment when we can say a given representation becomes conscious.

DCD: Yes. Dehaene sometimes calls that ignition. I think that’s a dangerous term because it suggests that there’s some huge phase shift that makes a huge difference. Well, there are phase shifts, but they are not the elevation so much into consciousness as they are the securing of more fame. The important point you have to remember is that an experience can be temporally punctate. It can have a very definite time course, it can be, ‘pop!’, just like that. But the fact that it’s an experience of a momentary ‘pop!’ doesn’t mean that there’s a moment when the pop becomes conscious and in a way we all know that.

Think the phenomenon of being engrossed in a book, in a room where there’s in fact a clock that has chimes and at some point the clock starts chiming and at about chime three you are distracted. You find you can retrospectively you can realize that, “Oh that’s chime three.” You weren’t aware of times one and two. You become fully conscious at time three but that’s when you become conscious of times one and two but they’re just as punctate. The time when consciousness happens as opposed to the event that you’re conscious of. That’s a very adjustable, variable thing.

“Hunting for the neural correlates of consciousness is like hunting for the biological correlates of speciation. There aren’t any.”

The same thing is true about speciation. You can’t tell when speciation is occurred until maybe thousands of years later. There’s just nothing that’s the case at the time when the two populations drift apart, that’s secured. Has there been speciation? We don’t know. We won’t know for another 150 generations at least. Speciation is a perfectly real physical event. It cannot be non-arbitrarily timed to the century in most cases and consciousness is the same way. That’s why hunting for the neural correlates of consciousness is like hunting for the biological correlates of speciation. There aren’t any.

HS: On a big picture note. I think we probably agree that over the last three decades in particular have seen incredible scientific progress in trying to understand the nature of consciousness in the brain. But do you think the finish line for the science of consciousness is in sight? Do you think within a decade or two more we’ll finally have the scientific theories and evidence in place to put this problem to bed? Or do you think it’s the kind of problem is always going to have dissenters, and is always going to be seen as unsolved by some in the scientific and philosophical community.

DCD: I think there won’t be a loud bang. There’ll be a whimper. Gradually, people will lose interest in the question of what exactly do scientists mean when they talk about consciousness because their curiosity will have been satisfied. Notice the same things happen pretty well with the question of ‘what is life?’ Don’t ask a biologist to define life. They’ll get very annoyed because, are viruses alive, or viroids, or are motor proteins alive, you have to have a metabolism, could a computer virus be alive… Yawn! There’s a whole bunch of different things. Nature’s full of tricks and you can call whatever bag of tricks you want life. As long as we understand the bag of tricks, we don’t need to draw the line. I think the same thing’s happening with consciousness. We’re going to understand more and more and more and more. The question ‘yes, but does consciousness extend down to the clam?’ will seem really silly because we’ll know all about clams and we’ll know all about lizards and bears and people. And the idea that there’s this one thing, consciousness, which is easily present or absent will no longer have a hold on us.

“The question ‘yes, but does consciousness extend down to the clam?’ will seem really silly because we’ll know all about clams… the idea that there’s this one thing, consciousness, which is easily present or absent will no longer have a hold on us.”

HS: That’s a very interesting way of thinking about how the future of consciousness research may go. I imagine many people will think that consciousness is still ineluctably important for moral reactions towards animals. Peter Singer has a famous example where he talks about how a schoolboy kicking a stone is doing nothing of moral significance because the stone can’t suffer. I think a lot of people have this very deep intuition that consciousness matters for things like suffering and moral patients in a way that other mental states don’t.

Certainly when I go for an invasive operation and I ask the doctors, “Well, under this anaesthetic, will I be conscious?”, and they say, “Well, your attentional faculties will be slightly modulated, you won’t be able to report on your mental states, and you’ll have the following cognitive alterations…” It seems that I still want to know, yes, but will I be experiencing conscious suffering? How do you see intuitions like that as faring fairing in two or three decades when maybe we have a better understanding of how consciousness works in the brain?

DCD: Well, I would expect that particular intuition about the surgery should fade and we already know why. Because modern anaesthesia is deliberately as shallow as they can get away with because it’s dangerous. It’s sort of reversible brain death. You keep people as lightly anesthetized as you can get away with. That means that in many surgeries there’s plenty of signs of consciousness, but there’s no squirming because they’ve given you a muscle relaxant or something like tubocurarine, which really paralyzes your muscles if they need to do, abdominal surgery, say, and of course they can give you amnestic so that you don’t remember it afterwards.

There’s a whole cocktail, it’s used by anaesthesiologists. Anaesthesiologists are already riding on a myth. You will be unconscious. We put you right to sleep. Don’t worry, you won’t feel a thing. Afterwards people say, yeah, right, I didn’t feel a thing. I didn’t even know what happened. Maybe you don’t want to know too much. It should have the effect of undercutting the obviousness that many people are so sure about with regard to that feeling that’s suffering and suffering is bad. I want to say yes, suffering is bad. There’s nothing worse than suffering, but now, what’s bad about suffering?

If somebody says, well, it’s just the intrinsic awfulness of it. No, that’s not even an honest answer. You’re just pulling intrinsic awfulness out of the thin air and, and not, that’s not solving a problem, that’s defining it out of existence. If you really want to know what’s wrong with that suffering, you have to think, well, what, what makes you suffer? And isn’t it in fact, your inability to do what you want to do and concentrate on what you want to concentrate on and enjoy what you want to enjoy? Is it the intrusiveness and the imperiousness of the interferences? That’s what suffering is.

HS: Do you think it’s something similar will apply to our attitudes towards animals? That rather than worrying about whether, for example, fish feel phenomenally conscious pain that instead we’ll move to a more incrementalist view of animal welfare?

DCD: Absolutely. Absolutely. I think that we have all the conceptual and empirical tools for distinguishing organisms in terms of their susceptibility to suffering, if you like. An interesting, if uncomfortable, fact for many people is that dogs are much more capable of suffering than wolves are. Why is that? They’re not physiologically that different. Of course, everything comes down to physiology and chemistry in the end, but they’re more capable of suffering because they’ve been domesticated to be capable of suffering. They’ve been humanized. They’ve been anthropomorphized unconsciously by the domestication process. A Wolf will gnaw off its own paw to get out of a trap. I don’t think a dog will do that.

HS: While we’re on the topic of animal minds, perhaps it’d be a good time to discuss this distinction you use to do a lot of work between competence and comprehension, using the example in your latest book of zebras, for example. Could you just say a little bit about what this distinction amounts to and how you put it to work?

DCD: Think of the fledgling cuckoo. It’s been hatched in a nest of adoptive parents. The Cuckoo’s mother has surreptitiously laid egg in a foster nest. The first thing that fledgling cuckoo does when it breaks through the shell – and\ it tends to break through the shell earlier than the other eggs, and there’s a reason for that – the first thing it does is it rolls the other eggs out of the nest. Why? Well, it’s not hard to see. It’s going to monopolize the food getting of its adopted parents. Does it know what it’s doing? Does it understand what it’s doing?

No, of course not, but there is a reason why it’s doing it and these are what I call free floating rationales. They are everywhere in nature. There’s reasons why ribosomes do what they do. There’s reasons why your immune system does what it does. There’s reasons why you sneeze. There’s reasons why motor proteins move the way they do inside your cells, but these reasons are not appreciated by the things whose actions are explained by those reasons. These are cases of competence without comprehension. I think nobody has any trouble with the idea that a motor protein doesn’t comprehend what it’s doing; it doesn’t have to, it’s competent without comprehension.

“I think nobody has any trouble with the idea that a motor protein doesn’t comprehend what it’s doing; it doesn’t have to, it’s competent without comprehension.”

Now, this is a hard thing for people to get their heads around because we’re taught in school. Why do you go to school? To comprehend, in order that you may be competent. We tend to think of comprehension as being the source and guarantor of our competence. That’s why we’re down on rote learning and things like that. But rote learning is actually very powerful. And even for human beings, very often, competence precedes comprehension.

If you want to really understand mathematics, you better have a flawless fluency with numbers, with counting, with addition and subtraction, multiplication and so forth. The competence comes first. Comprehension is a later add on. It is such a later add-on that one of the puzzles that I address in the book is, well, if all of this competence is available without comprehension, what do we need comprehension for? And that’s actually a good question and one of the things we have to recognize is that there’s a lot less comprehension out there than you might think.

HS: I realize you’re just giving a sketch of the theory for the purposes of this interview, but I worry that some of the audience might think of the comparison you drew between the ribosome and the cuckoo as suggesting that in both cases there’s just competence and there’s nothing that can qualify as comprehension. Surely, there are differences at the level of what we might call cognition? The cuckoo is doing something like figuring out the categorical identities of things and its environment, or at least developing some kind of perceptual associations. There’s a richer story to be told about its inner life.

DCD: Yes, but there’s what you might call behavioural comprehension. In fact, where does comprehension come from? It is the product of multiple layers of competence. The Cuckoo’s eyes don’t understand anything. The individual parts of the Cuckoo’s brain don’t understand anything, but the cuckoo has some behavioural understanding, but it can’t explain anything. The fact that it’s a baby doesn’t mean that well, when it’s grown up, it will understand.

The cuckoo mother doesn’t understand why she’s laying her eggs in that nest either. She’s very clever. She watches the host, targets and waits until they have laid their eggs and she waits till they’ve flown off. Then she swoops down surreptitiously and lays her egg in the nest. In some species, she will roll one of the eggs out. This is just in case the host can count. There’s an arms race going on there, but that doesn’t mean that the cuckoo understands. Even the adult cuckoo doesn’t understand what she’s doing, but they’re very competent.

HS: In one of your books (possibly my favourite), Kinds of Minds, you draw a distinction between different varieties of capacities that creatures have; between, for example, Skinnerian and Popperian creatures. That seems to point to the possibility of a rich field of distinctions to be drawn among different kinds of cognition that is present in different animals. Some philosophers like Tyler Berge frame this in terms of natural psychological kinds – the idea of looking for these sharp discontinuities between the capacities of different species across the phylogenetic tree. At least superficially, it seems like there’s maybe a tension between this kind of ‘sharp lines’ view of the distribution of cognitive capacities across nature and the thoroughgoing incrementalism that pervades your work. Do you see that as a superficial tension or a real one?

DCD: I see there’s a real tension. A new book, which very nicely explores that territory is by Eva Jablonka and Simona Ginsburg and it’s called The Origin of the Sensitive Soul. It’s full of detail about the phylogenetic paths from simplest bacteria up to human beings. They take my Popperian, Skinnerian, Darwinian, Gregorian quartet seriously and then some. What I haven’t done, and they’re doing (and a lot of it I sure they’re right about) is saying, it’s all very well to have these sharp lines, but we have to look at the transitions between them . What evolutionary path takes you from a Skinnerian creature to a properly Popperian creature to a properly Gregorian creature? I left those questions unasked, but they’re asking them and they are the right questions to ask. Back comes the gradualism, back come the intermediate cases and it’s just not biologically sound thinking to suppose that there are sharp lines. There are thresholds, but there’s always going to be lots of intermediate cases.

HS: One topic that will interest a lot of our listeners is artificial intelligence. Throughout your career, you’ve used AI as a tool for thinking about consciousness and intelligence. I was wondering your view of recent demonstrations of the capacity of deep learning such as the victory of AlphaGo over Lee Sedol. Are these key milestones in the development of truly intelligent machines and computers with the same capacities as human beings?

DCD: Yes and no. They are very important and surprising advances. Advances certainly I didn’t anticipate or predict and I was pretty much gobsmacked at the success of deep learning, particularly because I’d been in on the earlier connectionist work and the back-propagation work and all of that and realized the limitations of neural network models up to a certain point. Then along comes Jeffrey with his wonderful insights and now we have deep learning and it’s just stunning what it can do. The way I view that is, we now have a new batch of fabrics, epistemological fabrics that have amazing properties, but they’re not architectures and they’re not agents. They are just fabrics with capacity.

Now let’s see what we can make out of those. What can we tailor those into? How do we pile them up? How do we get them to feed into each other? How do we get them to reflect on each other? That’s still a long way away and people are working very hard on it. The people at Deepmind have got lots of good ideas about this that they’re pursuing at a feverish pace. A lot of smart people are working on it. I think they recognize from talking to them, I get the sense that they recognize that we’re not that close, that it’s still a long way off.

Let’s take a recent landmark. Not AlphaGo or Alpha Zero, going back just a little bit, let’s go to IBM’s Watson that wins at Jeopardy. Stunning achievement – but you can’t actually have a conversation with Watson. The communicative front end of that is paper-thin and, and it’s all pretty much candy. You couldn’t have a conversation with Watson; or you could, but only if they devoted another thousand person, centuries of brilliant work. I would say that Watson is to a genuine AGI – autonomous, conscious, intelligent, agent – roughly as an abacus is to Watson.

HS: As a cognitive scientist, do you see language, for example, as being particularly a challenging task? Your colleague, Douglas Hofstadter has written about the difficulties in achieving human-level linguistic comprehension and performance. Do you see that as an example of the kind of limitation you’re thinking of?

DCD: Yes. I’m glad you mentioned Doug because I think Doug has done some recent short pieces where he’s very critical of Google Translate for instance, and for good reasons. I think – not to deny the stunning competence of Google translate – there’s no comprehension yet. There’s orders of magnitude to go before we get to proper comprehension. It’s not that it’s impossible. AGI, conscious robots, that’s all possible, but it’s not on the near horizon.

HS: Even granting that AGI, human-level artificial intelligence, is not something that’s around the corner, what do you think of the ideas of people like Max Tegmark that AGI, when it does arrive, will constitute a radical new phase in the development of life on this planet – that it’ll be a new generation of replicators unlike anything seen before.

DCD: I think a version of that is true, which is why I argue that we should prevent that from happening. My motto is, “Smart tools, not artificial colleagues”. Smart tools, we can control. Artificial colleagues, we can’t. We are better off making smart tools and I have some early thoughts about how to do what is ultimately the political work and legal work of preventing the development of AGI. We don’t need AGI. There’s better things to do with the fabrics of AI than to make artificial colleagues, much better things to do. And besides, it’ll be much more fun because we’ll all have the thrill of making the scientific discoveries and the political decision-making and all the rest with the help of our smart tools and we will be responsible for good or for ill of what we do with that power.

“My motto is, “Smart tools, not artificial colleagues”. Smart tools, we can control. Artificial colleagues, we can’t.”

HS: We have just a few minutes left and I’d like to turn to a couple of broader questions about the role of philosophers in cognitive science and broader intellectual inquiry. So philosophy was one of the original six disciplines in the original hexagon of cognitive science. Do you think that in an era where so much research on consciousness, for example, is done by neuroscientists and psychologists using incredibly expensive neuroimaging machines, that philosophy still has something important to bring to the table?

DCD: Absolutely. We’re finally beginning to emerge from the simple-minded era of fMRI studies where people were going for the low-hanging fruit and there was an awful lot of ill-motivated and ill-interpreted data out there. People are finally wising up but they’re wising up because they’re beginning to appreciate some of the conceptual problems with the questions they’re asking. What I think philosophy at its best is really good at is getting people to ask slightly different questions, to be critical of their own questions, and recognize that there may be hidden assumptions in their questions that aren’t as obvious as they think. In fact, they haven’t even noticed that they’re making these assumptions.

Of course, my favourite is, in spite of what many neuroscientists assure me and they say, “No, no, I don’t believe this Cartesian theatre, I don’t believe there’s an inner theatre where the show goes on”. Then I look through their work and say, “Well then why do you say this? And why do you say this?” “Ah, I see what you mean.” They suddenly realize that what they’ve got is at best the theory of television, not vision.

HS: You are one of the few very few public intellectuals within analytic philosophy. To my surprise, very few active philosophers are household names these days. I wonder if you had a view on why this is and whether you think it’s a problem.

DCD: Well, I remember when I was a graduate student here in England, AJ Ayer was very much an urbane exponent of views on the BBC, on television and radio, and philosophers got more attention. He was pretty famous. There was nobody in the United States that occupied that role. It hasn’t been, I think, since John Dewey – that’s probably the last philosopher that had that public notoriety. Why? Because the field became more professionalized and somewhat ingrown. I’m of two minds about it.

On the one hand, I think that philosophers should in a way revel in their ivory tower isolation. I have a little piece called, “Philosophy as the Las Vegas of sciences”. What happens here, stays here. What happens in philosophy stays in philosophy. In philosophy you can talk about anything you want to. A lot of it, if it were out in the public, you’d have to start worrying about the environmental impact of these things.

It’s just as well that we don’t have the general public waiting for the latest word on whether there are circumstances in which it is all right to frame an innocent man or whether infanticide is beyond the pale or many of these other issues or whether the world really exists. People do these days get quite excited about whether we’re all living in the Matrix, whether we’re living in a simulation. Well, thank you philosophy. I think that’s basically a philosophical idea, not I think adding a whole lot to the public culture.

HS: Recognising that there’s value in the kind of ivory tower philosophy you’re describing, you did say in an interview with Prospect magazine a couple of years ago that a lot of philosophy these days is not worth your effort – which is surprising to me given that in philosophy of mind, at least it might look to an outsider, it might look to many people, that your style or philosophy, of philosophy of mind as informed so heavily by empirical evidence, has actually won out – that philosophy is very much closer to the kind of model that you yourself prescribed. Would you expand a little bit on why you think so much of it is not worth your effort?

DCD: Well, I don’t know what proportion is not worth my effort. I just know that there’s a lot which is good old-fashioned arm chair intuition-busting. That I think is just taking in each other’s knitting. It’s just artefactual puzzles, which you can demonstrate your cleverness in solving and then disputing. I warn my graduate students than others to stay away from that because it’s very seductive. And to put it really bluntly, I see some of my colleagues, not at my university but at others, who I think should have trouble sleeping at night when they realize they’re responsible for taking really smart young people and turning them into these artefactual puzzle mongers. It’s such a shame because it’s a waste of a mind.

HS: For any young philosophers out there listening, what would you say is a marker of a really valuable problem, rather than one of these artefactual puzzles? What kind of considerations should go into a decision about whether something is worth exploring?

DCD: Well, any simple rule of thumb can be exploited and you can find counter-examples too, but a pretty good one is to see if you can explain to a bunch of bright undergraduates who’ve never heard of it, why this is an interesting problem. If you have real difficulty explaining to them why it’s an interesting problem… it’s probably it’s not worth your time.

“A good rule of them is to see if you can explain to a bunch of bright undergraduates why something is an interesting problem. If you have real difficulty explaining to them why, it’s probably it’s not worth your time.”

HS: Finally, you just mentioned John Dewey, who had strong views on the role of education, and and I was just curious – obviously you’re justifiably famous for a long research career, but you’ve spent much of that career, as all academics do, serving as an educator. I wondered what you thought the role of philosophy was in broader education, particularly for people who aren’t going to go on to have academic careers. What can philosophy do for society? What should its responsibilities be?

DCD: Well, I think the same that I said for what it can do for cognitive science. It can help you ask better questions and it can teach you not just a knee-jerk scepticism and anxiety about getting the words exactly right. That’s sometimes very counterproductive. But just becoming actually more open-minded, extending your imagination, ‘imagination prostheses’, is what philosophy can be. It can help you imagine things you never thought of imagining before.

HS: Thank you so much for conducting this interview with us and sharing this discussion with on your ideas.

DCD: Thank you.

HS: Thanks to our audience for tuning in, and for more podcasts brought to you by the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, check out our website.

Leave a Reply